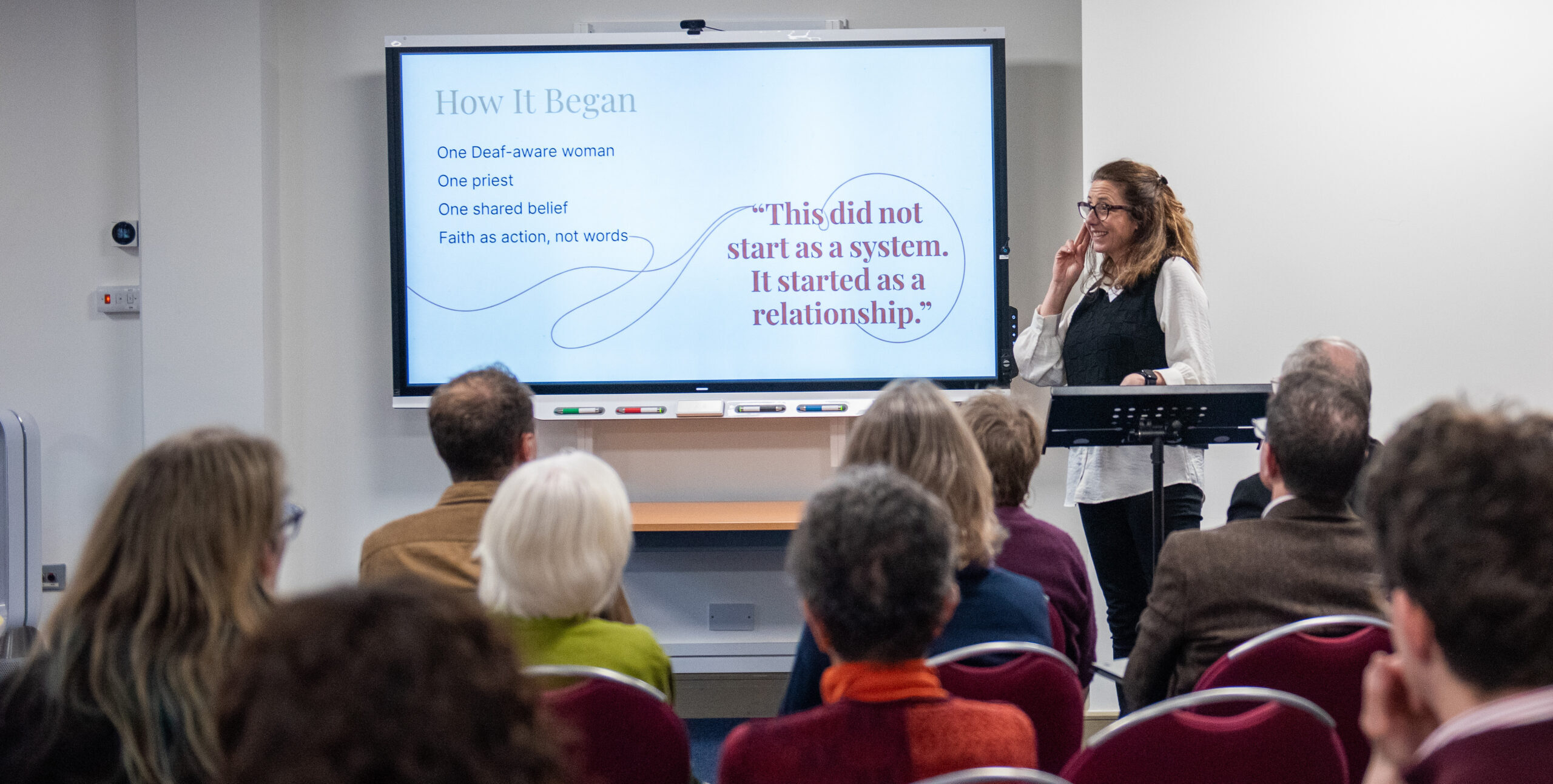

As we continue to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Signs of Hope, our counselling service in British Sign Language (BSL), Victoria Nelson, Deaf therapist and Signs of Hope counsellor, tells us about the importance of enabling Deaf people to access different forms of mental health support in BSL.

When I read Sally Austen’s article on The Limping Chicken about deaf mental health services, I found myself nodding along. She’s absolutely right: the system we have doesn’t make sense. In some places, it barely functions at all.

But as I read, another question kept nagging at me. There is something missing here — something bigger than just the psychiatric response to complex mental health problems.

Where is the rest of the mental health system?

It can’t just be psychiatry or nothing. Deaf people deserve the same full spectrum of support that hearing people get — not the mental health equivalent of “take it or leave it” which seems to be the current situation. Right now, we don’t have it.

Hearing people get to choose from a massive menu of support. Depending on their needs, they can access:

- Counselling

- Psychotherapy

- Trauma therapy (EMDR, etc.)

- Faith- or spirituality-informed therapy

- Minoritised or global majority racial or cultural identity specialists

- LGBTQ+ specialists

- Disability specialists

- Domestic abuse support

- Neurodiversity specialists

- Psychiatry

- Or any mixture of these.

And Deaf people?

Often, we are handed a single option and told: “Here you go. Hope it works. If not… well…”

It’s the mental health equivalent of walking into a restaurant and the waiter saying: “We only have baked beans. No sides. No substitutions.” If you don’t like baked beans — or if your specific problem requires something else —you starve.

Many deaf people don’t need heavy psychiatric treatment. Conversely, many need much more than the remote, low-intensity access provided by services like SignHealth. We need the middle ground. We need the menu.

Because the NHS fails to provide this, the deaf community has had to build what the system wouldn’t. That is why deaf-led services like Deaf4Deaf and essential support from organisations like Signs of Hope are vital.

Why psychiatry falls short

A bit more honesty about mainstream psychiatry — the real problem is hiding in plain sight!

The challenge isn’t simply “psychiatry is medicalised.” There are problems across the whole NHS mental health system — not enough staff, not enough time, too much pressure.

It’s deeper. Here’s the uncomfortable truth: many hearing professionals do not fully understand deaf trauma — and frankly, some don’t want to understand it too deeply. Not because they don’t care, or because they are bad at their jobs. But because really understanding deaf trauma means facing uncomfortable facts:

Their own hearing privilege.

The fact that the hearing world caused much of this distress.

The devastating impact of language deprivation.

How education systems excluded us.

That is uncomfortable. When people feel uncomfortable, they build emotional distance, defences or walls. They say things like: “I must stay objective,” or “I shouldn’t get too involved in deaf culture.”

It sounds professional. But often, it’s just a way to avoid seeing what it really means to be a deaf child growing up unheard, excluded and isolated. Repeatedly. That’s a trauma. A complex, developmental deep trauma that many hearing people just don’t understand.

Because if a clinician truly admits the source of the trauma, they have to accept that the “symptoms” aren’t illness. They aren’t “behavioural issues.” They are the result of lack:

Lack of access.

Lack of language.

Lack of belonging.

The system labels this as “emotional dysregulation” or “attachment issues.” We call it a lifetime of being left out, ignored, put down and misunderstood.

This is why deaf-led, deaf-informed trauma-aware support is not a luxury. It is a necessity. Deaf therapists don’t have to protect themselves from the reality of deaf trauma. We recognise it. We’ve lived parts of it. We don’t turn it into a pathology—we turn it into insight.

We are not just “Deaf”

The system constantly forgets that deaf people are complex. We have races, cultures, sexualities, faiths, and neurodiversities.

Hearing people can find a therapist who understands their specific background. But deaf people are expected to be grateful for anyone who can sign “Hello,” thumbs up, and finger-spell their name.

A deaf domestic abuse survivor shouldn’t have to choose between a deaf therapist or a trauma specialist. A deaf Muslim client shouldn’t have to choose between a faith-informed therapist or a deaf-aware one. We deserve both. That is what an intersectional deaf mental health system looks like.

The value of lived proximity

While deaf-led expertise must be at the centre, we shouldn’t push away those with “lived proximity.” I’m talking about CODAs (Children of Deaf Adults), siblings, hearing parents who fought for access, and partners who live inside deaf culture.

A CODA who navigated two cultures since childhood? They get it.

A sibling who watched you being left out of every dinner table conversation? They get it.

A parent who fought the school system? They get it.

Their insight isn’t the same as being deaf, but it is real, deep, and valuable. It’s not about replacing deaf voices; it’s about widening the circle to include the people who actually understand.

Why Deaf-led therapy feels like “coming home”

In deaf-led therapy, you don’t have to explain the basics. You don’t have to explain why childhood felt like a series of empty rooms, or why “I’ll tell you later” still stings.

We get it before you’ve said a word.

We don’t need subtitles for your feelings. Deaf-led services are often the only place where deaf people can bring their whole selves without shrinking.

So, what does a better system look like? It isn’t just one door. It’s a network: Deaf-led counselling and psychotherapy; Deaf-aware psychiatric services. Specialist support for everything else: addiction, ageing, fertility, gender identity, and neurodiversity. Proper funding and training routes for deaf therapists.

Sally Austen opened the conversation. Now we need to widen it.

We need to bridge the massive gap between high-level psychiatry and low-level primary care. We need safety, options, and support that sees our whole identity.

Deaf4Deaf and others will keep pushing for that future. We’ve survived on scraps long enough—it’s time for the whole menu.

Victoria Nelson is a Deaf UKCP-registered psychotherapist and Director of Deaf4Deaf, an award-winning therapy and counselling service for Deaf people. She specialises in trauma, identity, and Deaf mental health, and is developing Deaf-centred supervision models used across the UK. She has also recently joined the counselling team at Signs of Hope.