Richard Harries, Director of Caritas Westminster, reflects on how Pope Benedict XVI’s Deus Caritas Est has shaped the presence of Caritas agencies in England and Wales in the 20 years since the encyclical’s publication.

When Pope Benedict XVI published his first encyclical, Deus Caritas Est, twenty years ago, it was a rescue mission. His predecessor, Pope John Paul II, had called in his final years for “a new creativity in charity … shown not only in more efficient forms of charitable assistance but even more in an ability to be close to those in need” (Pastores Gregis, §73). Despite two millennia of Christian charity, the Holy Fathers had discerned a deep void at the heart of the Church’s institutional response to Christ’s commandment to love our neighbour.

Benedict’s encyclical speaks powerfully of the Church’s “deepest nature” being expressed in her threefold responsibility: to proclaim the word of God, to celebrate the sacraments, and to exercise the ministry of charity. “These duties presuppose each other and are inseparable.” (Deus Caritas Est, §25). Part 2 of the encyclical is a virtual instruction manual on the form and structure that diocesan Caritas agencies are to take and spells out with almost clinical precision what Rome expects to see.

To fully grasp the implications however, Deus Caritas Est needs to be read alongside two other Vatican documents: Apostolorum Successores (the Directory for the Pastoral Ministry of Bishops published in 2004) and Intima Ecclesiae Natura (the apostolic letter issued motu proprio in 2012). Taken together, this magisterial trinity presents a complete blueprint for every diocesan bishop to follow, and it is instructive to compare their prescriptions with the situation in England and Wales, not least since our provinces were some of the last in the Catholic world to adopt the formal structures of Caritas that are so common elsewhere.

Let us begin at the beginning, with Chapter 7, Part 4, of Apostolorum Successores:

To facilitate aid for the needy in the most effective manner, the Bishop should promote a diocesan branch of Caritas … which, under his guidance, animate[s] the spirit of fraternal charity throughout the diocese.

At the same time, insofar as possible, the Bishop should establish in each parish setting a branch of Caritas … which together with those on the diocesan level, can serve as the instrument for coordinating and animating the exercise of Christian charity in the parish community.

So how have we done? Over the last two decades, fully 17 of the 22 dioceses in England and Wales have established some form of diocesan Caritas agency, and three more (in Birmingham, Liverpool and Leeds) have co-opted a local charity to act on their behalf in persona caritatis. The two largest Caritas agencies are Caritas Salford (an independent charity chaired by Bishop John Arnold, with a turnover of £3.8 million) and my own Caritas Westminster (a ringfenced agency within the Diocese of Westminster chaired by Bishop Paul McAleenan, with a turnover of £3.2 million). The youngest is Caritas Southwark which was launched in March 2023 under the leadership of Canon Victor Darlington.

Of course, it is one thing to set up a new structure, quite another to make a difference in the real world. So what is the remit of a diocesan Caritas agency? What does Mother Church mean when she talks of “coordinating and animating the exercise of Christian charity”? Here we must return to Deus Caritas Est:

Christian charity is first of all the simple response to immediate needs and specific situations: feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, caring for and healing the sick, visiting those in prison, etc.

Love of neighbour, grounded in the love of God, is first and foremost a responsibility for each individual member of the faithful, but it is also a responsibility for the entire ecclesial community at every level … Love thus needs to be organised if it is to be an ordered service to the community.

The Church’s charitable organisations, beginning with those of Caritas … ought to do everything in their power to provide the resources and above all the personnel needed for this work.

Elsewhere in the encyclical, Benedict emphasises that “charity is not a kind of welfare activity which could equally well be left to others but is a part of [the Church’s] nature, an indispensable expression of her very being.” (Deus Caritas Est, §25) The message is clear: every Catholic parishioner has a personal responsibility to attend to the immediate needs of their neighbour, and the parish and diocese must do all they can to put in place structures that allow this to happen.

The encyclical is equally clear about what Caritas agencies should avoid:

Christian charitable activity must be independent of parties and ideologies. It is not a means of changing the world ideologically, and it is not at the service of worldly stratagems, but it is a way of making present here and now the love which man always needs…

This firm proscription surprises many who are familiar with the modern, secular world of campaigning charities. It is certainly not meant as a restriction on the prophetic voice of the Church. It is simply prioritising the literal interpretation of the Good Samaritan parable over the analogical. The Samaritan on his journey from Jerusalem to Jericho did not pause to decry the hegemonic Roman control of the Judean economy; he simply paid the innkeeper with two denarii struck with Caeser’s image. His response was immediate and it was personal. And when Jesus says at the end of the parable, “Go and do likewise”, it is a direct instruction to the inquisitive lawyer – and to all of us.

There are of course many other channels for the Church to speak out against injustice, not least through the offices of the Bishops’ Conference and through its national justice and peace network. And indeed, following Isaiah, we must “Cry aloud; do not hold back; lift up your voice like a trumpet; declare to my people their transgression, to the house of Jacob their sins.” (Isaiah, 58:1)At the same time, Benedict warns against starry-eyed utopianism, noting that: “There is no ordering of the State so just that it can eliminate the need for a service of love.” (Deus Caritas Est, §28)

Where Apostolorum Successores and Deus Caritas Est fix the essential superstructure of the diocesan Caritas agency, it falls to the third document, Intima Ecclesiae Natura, to translate this into canon law, spelling out in black and white the legal obligation on bishops which includes:

Art. 8. – Wherever necessary, due to the number and variety of initiatives, the diocesan Bishop is to establish in the Church entrusted to his care an Office to direct and coordinate the service of charity in his name.

Art. 9. – The Bishop is to encourage in every parish of his territory the creation of a local Caritas service … aimed at fostering a spirit of sharing and authentic charity.

The final piece of the jigsaw is, of course, how all of this will be paid for. The Vatican’s gentle but firm advice is that “It would be a clear testimony to the spirit of the Gospel if priests and ecclesiastical institutions, led by their Bishop, were to commit themselves to allocating a fixed percentage of their annual income to charitable causes within the local or universal Church.” (Apostolorum Successores, §73).

So how does the Catholic Church in England and Wales measure up against these expectations? As Director of Caritas Westminster, I will limit my remarks to the Diocese of Westminster, which spans 30 local authority areas and is home to 5½ million souls. Around one in twelve are Catholic, of which 110,000 attend Mass every Sunday. In line with Deus Caritas Est, our vision is of the Church fully engaged in the ministry of charity, attending to those at greatest risk of exclusion through poverty, disability, isolation and exploitation.

We seek to do this in many ways. At our core is the work we do day in, day out with priests and parishioners across the diocese to increase the range, impact and visibility of Catholic social action. We also offer six bespoke services:

- Caritas Bakhita House, a safe house for women who have been trafficked, enslaved and exploited.

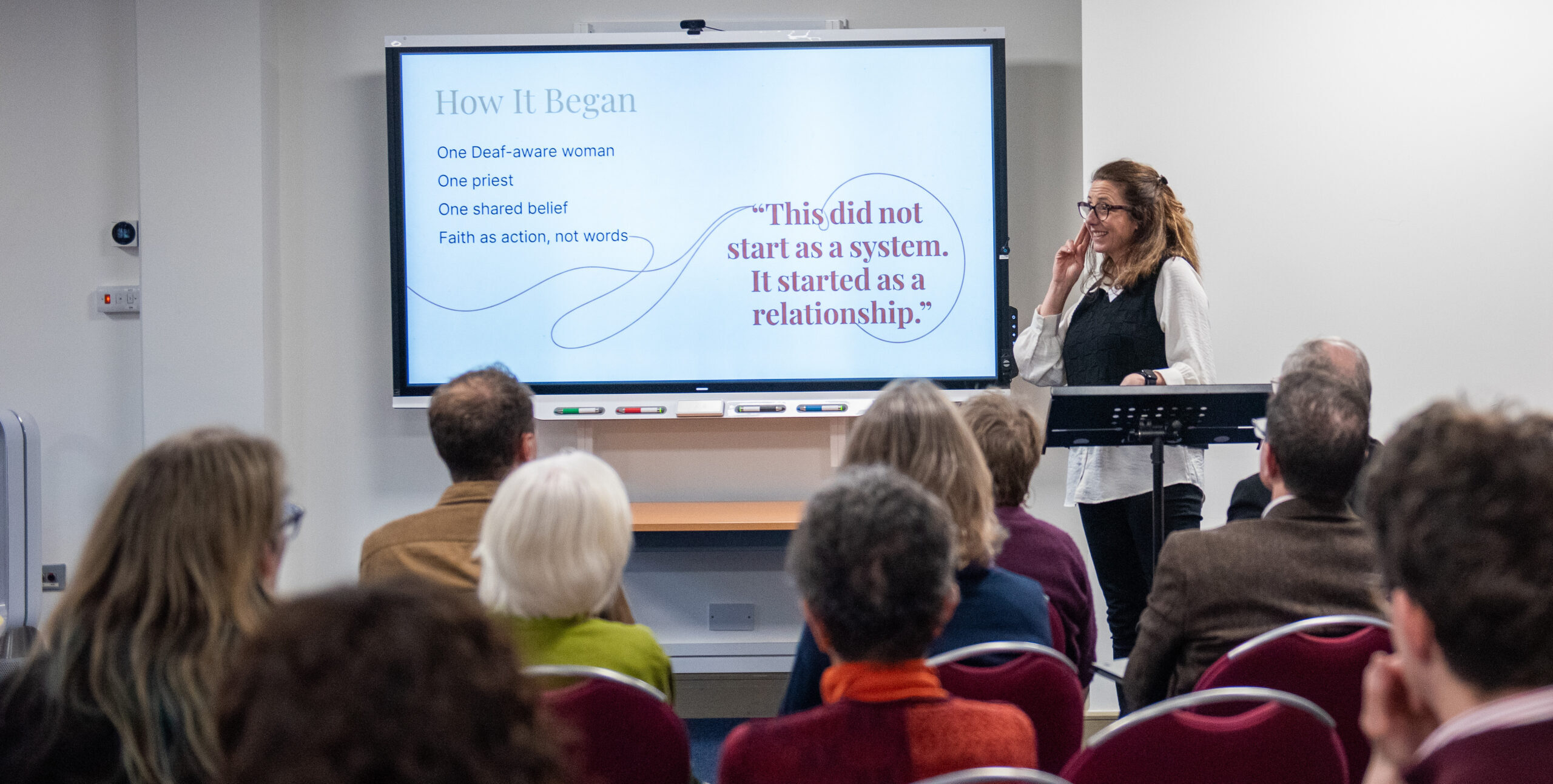

- Caritas Deaf Service, ensuring Deaf Christians receive vital pastoral and spiritual support to enable them to live full and dignified lives.

- Caritas Enterprise, supporting people across the diocese to set up social enterprises.

- Caritas Hope, a composite service providing counselling and psychotherapy for the Deaf community and promoting faith-sensitive support for people experiencing domestic abuse and gender-based violence.

- Caritas St Joseph’s, our learning and support service for people with physical and intellectual disabilities.

A question I am asked frequently is: “How is Caritas different to the all the other Catholic charities? How are you different to the SVP for example?” Yet to compare Caritas Westminster to the SVP is to miss the point entirely. It is like comparing the soil to the vineyard. Our task is not to grow grapes but to provide the nutrients that allow grapevines to flourish. And not just grapes; we want to see fields of wheat too, bearing fruit thirty-fold, sixty-fold, a hundred-fold. We want every Catholic charity in the Diocese of Westminster to thrive and so we do whatever we can to help them: finding office space, directing parishioners their way, and encouraging them to collaborate for the common good.

The point is this: Caritas Westminster is not just one more Catholic charity that happens to be operating in North London and Hertfordshire, we are the voice of charity in the diocese. Indeed, we are the voice of the Bishop fulfilling his pastoral responsibility as president of the assembly and minister of charity in the Church. In the more prosaic, technical language of the mainstream voluntary sector, we are an infrastructure organisation, providing support, coordination, representation, and capacity-building services to others; enabling them to operate more effectively and sustainably.

Which brings me on to a second question that more people should ask me but for some reason don’t: “Why does Caritas run services like Bakhita House? Aren’t you competing directly against other modern slavery charities like the Medaille Trust?” The answer here is more nuanced. Caritas Westminster runs services for three reasons: practical, pastoral and prophetic. The practical and the pastoral are best represented by our Deaf Service. It is a bitter truth that no-one else cares enough to make sure this isolated and excluded group of Christians receives access to the sacraments, let alone helps them sort out their council tax bills or visits them in hospital. We do. Because we can. And because it is the right thing to do. Because we are called to offer an “organised response to immediate need and specific situations”.

Caritas Bakhita House, by contrast, falls into the prophetic category. We seek to complement the work of great charities like the Medaille Trust, not compete with them. Whereas they are able to operate at scale through the substantial funding they receive from the government under its Modern Slavery Victim Care and Coordination Contract, our funding is entirely voluntary. Our mission is not to solve the disgrace of modern slavery but to show what is possible when the dignity of the individual is placed at the heart of service provision, wholly unconstrained by the limits of public procurement.

There is more work to be done to complete the rescue mission launched by Pope Benedict all those years ago. One area where Caritas Westminster falls furthest from Benedict’s vision in Deus Caritas Est is in our outreach to parishes. Of those 110,000 practicing Catholics in the diocese, barely 6,500 currently volunteer to support their local communities. Put another way, in a typical parish of around 500 parishioners, fewer than 30 engage in some form of social action through their church. We need to this to change. We need a Church fully engaged in the ministry of charity. Where the sight of Catholics serving their local communities is the norm, not the exception. Where each of us, after Mass, goes out into the world and truly seeks to glorify the Lord by our lives.

This article was originally published in The Tablet.

Image: Mazur/cbcew.org.uk